Tuesday, July 5, 2016

This Is a Portrait If I Say So: Identity in American Art, 1912 to Today

The Bowdoin College Museum of Art (BCMA) will present the first-ever exhibition to examine the emergence and evolution of symbolic, abstract, and conceptual portraiture in modern and contemporary American art. Titled "This Is a Portrait If I Say So: Identity in American Art, 1912 to Today", the exhibition takes its name from

Robert Rauschenberg´s renowned 1961 portrait of Iris Clert—a telegram that simply states, “This is a portrait of Iris Clert if I say so.”

On view June 25-October 16, 2016, the show includes more than 60 non-figurative portraits that pose provocative questions about what a likeness is; how a person’s individuality might be expressed effectively by another; how much a portrait can be influenced by the artist’s, as opposed to the subject’s, personality; and the very conceptualization of personal identity.

Covering more than a century of artistic development in the U.S., the exhibition features a broad range of media, including collages, drawings, new media works, paintings, photographs, prints, sculptures, and text-based conceptual portraiture, loosely divided into three chronological sections:

The first focuses on works from the 1910s and 1920s, assembled by Jonathan Frederick Walz, Director of Curatorial Affairs & Curator of American Art, The Columbus Museum, Columbus, Georgia . This section highlights artists such as Charles Demuth, Marcel Duchamp, Marsden Hartley, Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, Francis Picabia, Man Ray, Gertrude Stein, and their contemporaries.

The second is dedicated to works from the early 1960s to 1970, selected by independent curator Kathleen Merrill Campagnolo, and featuring works by artists such as Eleanor Antin, Mel Bochner, Walter De Maria, Robert Morris, Yoko Ono, and Robert Rauschenberg among others.

The final section centers on works from the early 1990s through today, curated by Anne Collins Goodyear. This concluding section includes works by artists such as Janine Antoni, Mel Bochner, Roni Horn, Byron Kim, Glenn Ligon, Hasan Elahi, L.J. Roberts, and more.

By focusing on specific periods, the curators are able to delve into the political and social realities that shaped American identity across these decades, and to unearth the distinct relationships, imagery, and themes that characterized the work of many major artists engaged with creating new modes of portrayal. The exhibition’s chronological installation reveals intriguing parallels between these three time periods, revealing dynamic through-threads within the artistic depiction of identity from 1912 to the present, such as the turn to language, symbolic attributes, and the metaphorical significance of color and form.

Some of the earliest examples of conceptual portraiture in the show reflect Americans’ awareness of the political turmoil in Europe during WWI, and the fluidity between artistic and intellectual circles on both sides of the Atlantic. Exhibition highlights from this period include

One Portrait of One Woman, a 1916 portrait of Paris-based American writer Gertrude Stein by Maine-born artist Marsden Hartley, who lived in Europe from 1912-1916. Replete with mystical symbols, the painting shows a blue teacup atop a checked tabletop, with the word “MOI” written boldly beneath, addressing the respective identities and complex friendship of the artist and sitter.

Another American with strong ties to Parisian intellectual circles who features prominently in the exhibition is Charles Demuth. Demuth and Hartley knew each other well, as evidenced by another highlight from this section,

Study for Poster Portrait of Marsden Hartley (c. 1923–24). The watercolor and graphite composition, which depicts a windowsill in front of a bright, snow-covered landscape, uses objects Demuth associated with his friend to capture Hartley’s persona.

“In the early twentieth century the general public often linked portraiture to flattering transcription and middle-class values; the genre provided strict, longstanding conventions that some modernist artists chose to bend or break,” said Walz. “Political and cultural shifts, including the development of an avant-garde and the breakdown of the traditional organization of sexuality, gave rise to themes that found continual expression in unconventional portraits throughout the century. For example, Gertrude Stein’s 1909 prose poem portraits presage Mel Bochner’s thesaurus-based likenesses of the 1960s and Charles Demuth’s poster portraits resonate with L. J. Roberts’s recent embroidery Portrait of Deb from 1988–199?.”

By the 1960s, the New York art scene was embracing Neo Dada, Fluxus, Pop, Minimal, and Conceptual art as alternatives to Abstract Expressionism. The eruption of new modes of expression coincided with a surge in the production of unconventional portraits. “While portraiture could not be considered a dominant genre during this decade which is often characterized by artworks that attempt to eliminate subjectivity and embrace systematic strategies for art-making, an undercurrent of interest in issues of identity can be seen in the work of a number of prominent artists of the period,” commented Campagnolo. “For the most part, the radical portraits of the 1960s feature subjects who were at the forefront of innovation in their chosen fields be it art, dance, music, or writing and offer surprising insights regarding the artist, subject, and historical moment.”

In addition to the exhibition’s namesake, highlights in the show from this period include

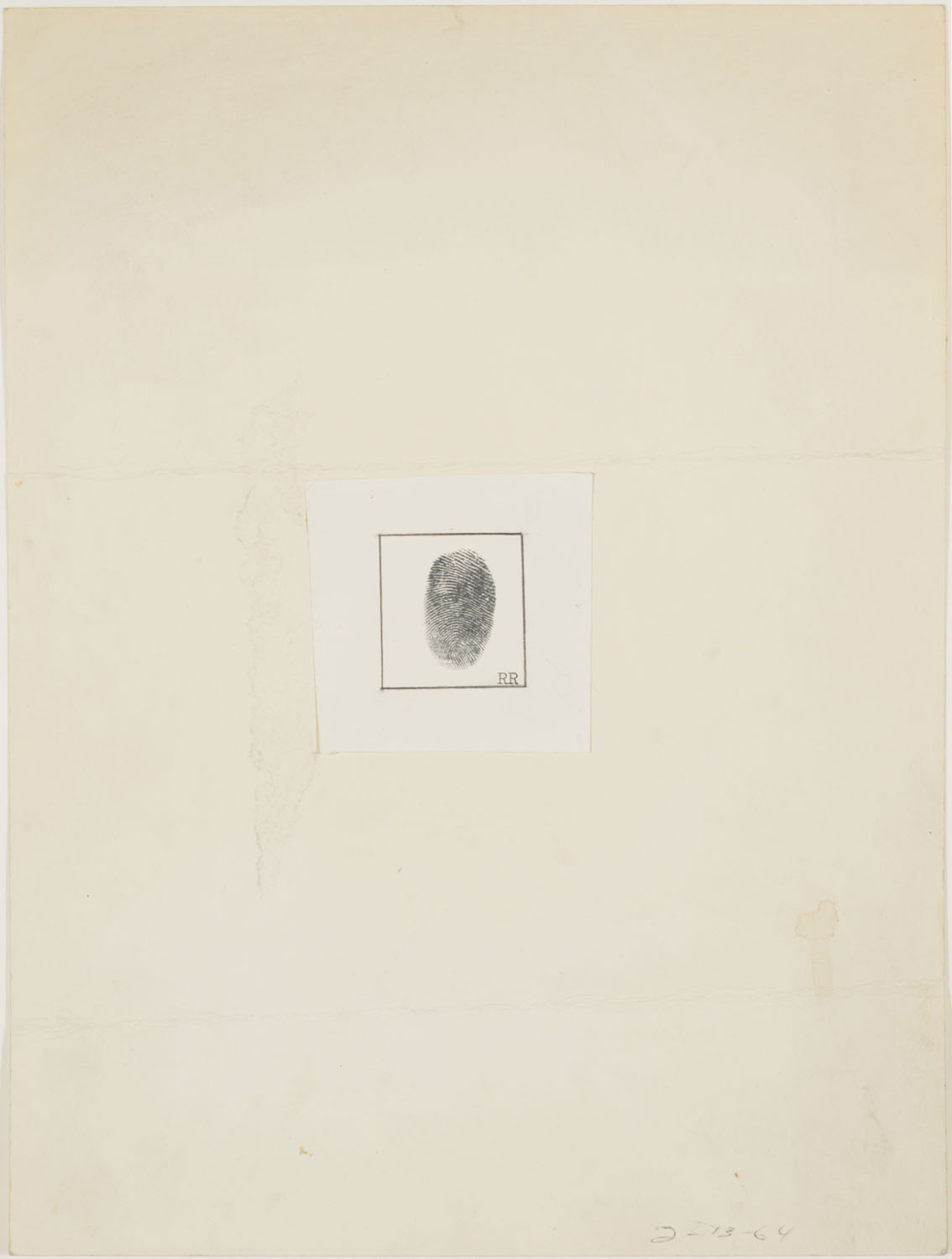

Rauschenberg’s 1964 Self-Portrait consisting of his thumbprint in ink and graphite on paper, created for a profile of the artist in The New Yorker.

Several of Robert Morris’ conceptual portraits are featured, including a cabinet-like sculpture containing labeled bottles of bodily fluids from 1963, simply titled Portrait.

Also present is Yoko Ono’s Portrait of Mary, a text-based call to action from her ground-breaking book Grapefruit, inviting viewers to examine and expand their assumptions about how identity is represented.

Exhibition highlights from the 1990s through today reflect artistic responses to developments like the emergence of the AIDS crisis, the decoding of the human genome, and the violent destruction of events on September 11th, which profoundly affected the expectations, demands, and the even the politics of the self and its representation. Glenn Ligon’s Runaway series from 1993 is a conceptual self-portrait consisting of contemporary descriptions of the artist juxtaposed with images garnered from advertisements of runaway slaves. Ligon turned to friends to provide the captions for this 10-work series, which vary so widely the notion of unified identity is called into question.

"Emmett at Twelve Months #3,: 1994, egg tempera on panel, by Byron Kim, born 1961. Collection of the Artist. © The Artist / Image Courtesy James Cohan Gallery, New York and Shanghai.

Artist Byron Kim contributed one of the captions, underscoring the evolution of non-figurative portraiture within influential artistic circles. Kim’s work is also featured in This Is a Portrait If I Say So, and he will create a site-specific work for the exhibition.

Roni Horn’s Asphere (1986/1990) represents another highlight from this section. A non-symmetrical sculptural form that resists easy categorization, the work metaphorically represents the artist, who identifies with its emphatically non-conventional nature.

“From the early 20th century up to the present day we see the adoption of abstraction as a strategy for portrayal that resists the cooption of likeness for political or social purposes,” said Goodyear. “We can trace this theme throughout the exhibition—a testimony to the power of the use of non-traditional symbolic and conceptual portraiture as a means to reclaim the representation of self and other from inherited formulas that may threaten to suppress rather than express what it means to a unique individual.”

The exhibition will be accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue published by Yale University Press. Featuring essays from Campagnolo, Goodyear, and Walz that examine their respective time periods in-depth, the catalog will also include a contribution from Dr. Dorinda Evans, professor emerita at Emory University, discussing the evolution of non-figurative portraiture in American art in the 19th century up until The Armory Show.